柠檬酸(citric acid)为无色、无臭颗粒粉末,具有强烈酸味,为动植物体内的天然成分和生理代谢的中间产物,是一种非常重要的平台化合物[1],也是当前世界上产量和消费量最大的食用有机酸[2]。柠檬酸主要合成方式为微生物发酵法,约有99%的产品是采用此方法生产[3]。因为丝状真菌黑曲霉有酶系丰富、发酵效率高、副产物少等优势,所以在工业化生产中,超过80%柠檬酸产品是由黑曲霉液体深层发酵获得[4]。但在液体培养体系中,其独特的形态学特征会显著影响产品的产量。因此,以黑曲霉为代表的丝状菌形态学解析、塑造及其调控一直是现代工业发酵研究的热点[5]。

1 菌丝球形成机理

在液体培养体系中,与细菌、酵母发酵过程相比,丝状真菌黑曲霉呈现复杂的形态学特征,如高度游离的菌丝,菌丝缠绕疏松的菌丝团以及菌丝缠绕紧密的菌丝球[5];在搅拌条件下的液体培养体系,更易产生非均相体系,影响耗氧发酵的两个关键过程——溶氧(dissolved oxygen)和传质过程(mass transfer),进而影响菌体生长和发酵产率[6]。在柠檬酸工业化生产中,发酵菌种黑曲霉孢子扩大培养需要经平板筛选、斜面培养、茄子瓶培养、麸曲桶培养等逐级扩大培养获得成熟的孢子,如图1所示,制备过程繁琐且周期长(制备周期超过30 d);然后在液体培养体系中获得成熟的种子。

图1 工业化规模产柠檬酸黑曲霉的扩大培养 Fig.1 Expanding cultivation of A. niger producing citric acid cultured in industrial scale

由于在连续培养过程中黑曲霉特殊的菌丝体结构,会造成溶解氧运输受到限制,进一步导致细胞代谢与柠檬酸合成异常,柠檬酸生产仍然以分批发酵模式存在,其能效较低,已成为柠檬酸产业提升的瓶颈。

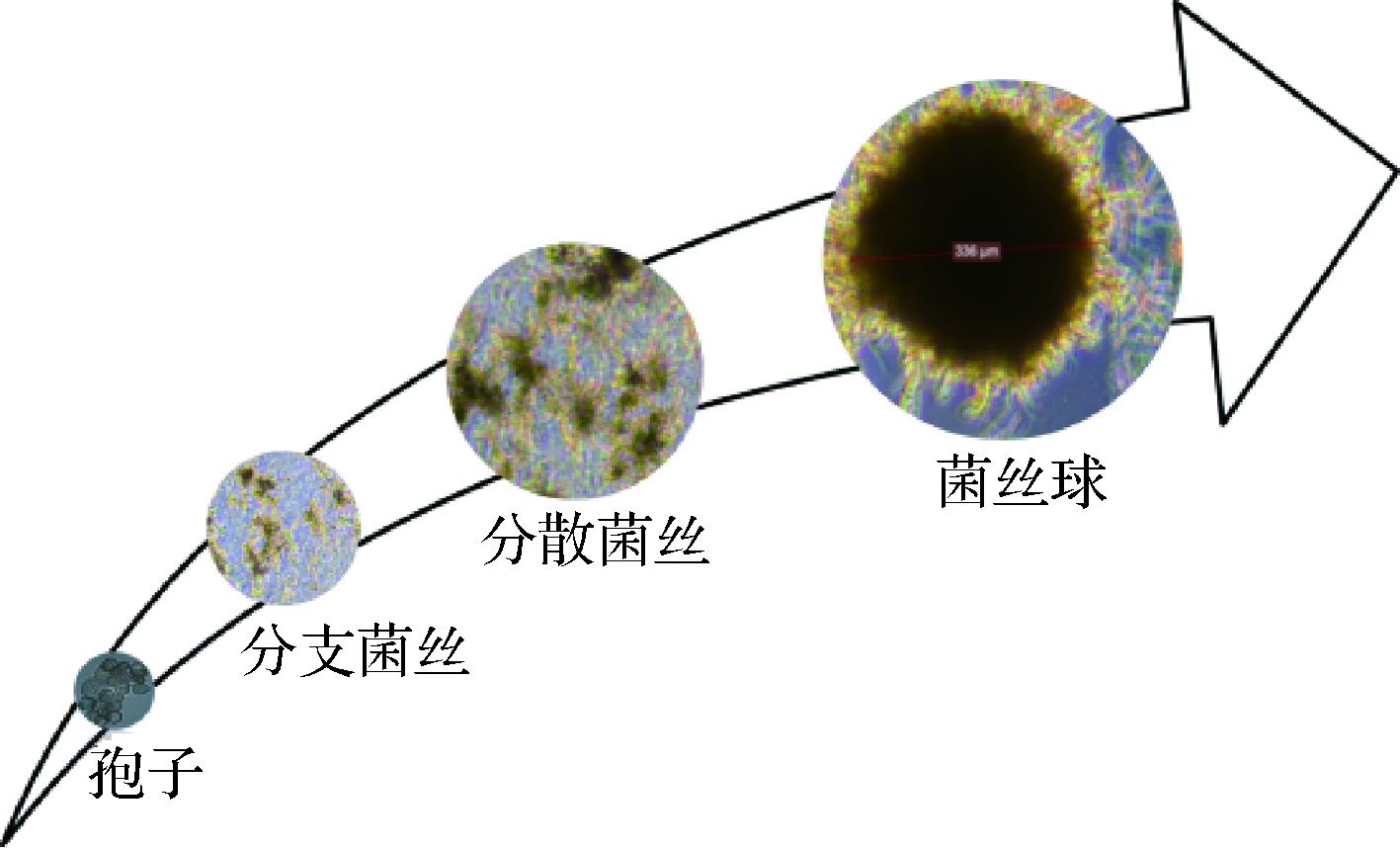

丝状真菌首先由休眠孢子吸水膨胀,逐渐萌发形成菌丝,菌丝进一步生长,形成大量的游离菌丝,游离菌丝相互缠绕形成菌丝球,图2为产柠檬酸黑曲霉液体培养时的形态学特征。根据孢子在萌发初期的聚集特性,菌丝球形成机制可分为非凝集性(non-coagulating type)和凝集性(coagulating type)两种类型[7]。非凝集型孢子的菌丝球形成会受到孢子浓度影响,低接种量会加速菌丝球形成。孢子聚集过程受到培养基组成、孢子活力、接种量以及机械搅拌因素的影响,主要发生在两个阶段:(1)接种后发生聚集,此过程仅受到渗透压和pH值影响;(2)萌发后发生聚集,不仅受到渗透压和pH值影响,还受到通气和搅拌的影响。在丝状真菌的液体培养体系中,只有准确把握孢子聚集类型以及其接种量,才能准确评估菌体的形态学特征。

图2 产柠檬酸黑曲霉液态培养时的形态学特征 Fig.2 Morphological characteristics of A. niger producing citric acid when cultured in liquid culture

2 形态学分析

丝状真菌形态学特征可分为微观形态学特征和宏观形态学特征。微观形态学特征直接受到发酵环境的影响,它是宏观形态学特征的外观呈现。在液体培养体系中,菌丝团或菌丝球的培养形式,可以降低发酵液黏度,提高传质与溶氧过程,同时利于菌体与产品的分离;但菌丝球核心与营养物质的运输存在限制扩散,形成生产率下降的“盲区”[5]。在工业化生产中,游离菌丝状的培养方式改善细胞生长速率与产率比较常见,但对于柠檬酸发酵生产来说,菌丝团或菌丝球更适合[8]。菌丝球的宏观生长表现为菌丝球半径的增加,但随着菌丝球半径的增加,发酵体系营养物质至菌丝球内部运输受到限制,因此菌丝球存在临界半径[9]。精确界定菌丝球的临界半径,对于准确控制发酵过程具有重要的意义。为了正确表征菌丝球的宏观形态学特征,EMERSON [10]首先提出了菌丝球的生长模型-立方根定律,菌丝球壳芯的宽度恒定,壳芯生物量因底物限制而不参与生产过程,其生长仅发生在菌丝球壳外围,以恒定的比生长速率生长,直至菌丝球临界半径。此模型的提出为定量分析丝状真菌形态学特征奠定了基础。

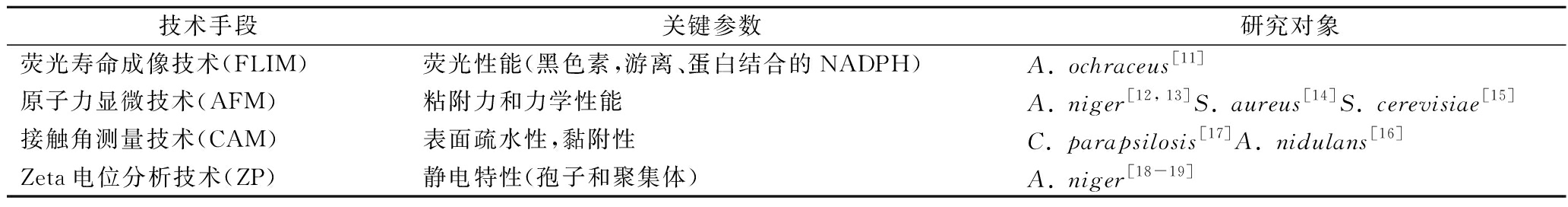

丝状真菌形态学在发酵过程中扮演重要角色,无论菌体微观形态(纤维状结构)还是宏观形态(菌丝球形态),均会影响柠檬酸发酵过程。正因为丝状真菌菌丝体形态学的重要性,定量分析丝状真菌形态的技术与手段,能够为研究者提供精细的形态学特征资料,为深入理解形态学特征与产物合成速率提供了依据[8]。近年来,定量分析菌丝的微观形态学取得了重要进展。如表1所示,荧光寿命成像技术(fluorescence lifetime imaging, FLIM)定量分析了黄曲霉的荧光性能[11];原子力显微技术(atomic force microscopy, AFM),定量分析了黑曲霉(Aspergillus niger)[12-13]、金黄色葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus aureus)[14]及酵母细胞(Saccharomyces cerevisiae)[15]的黏附力和力学性能;接触角测量技术(contact angle measurement, CAM),定量分析了构巢曲菌(Aspergillus nidulans)[16]与近平滑念珠菌(Candida parapsilosis)[17]的表面疏水性与黏附性;Zeta电位分析技术(zeta potential, ZP),定量分析了黑曲霉(A. niger)孢子及其聚集体的静电特性[18-19]。微观形态学特征的发展,为深入理解丝状菌的宏观形态学特征提供了参考。

表1 菌体微观形态学特征分析的研究进展

Table 1 Research progress of microbial morphological characteristics

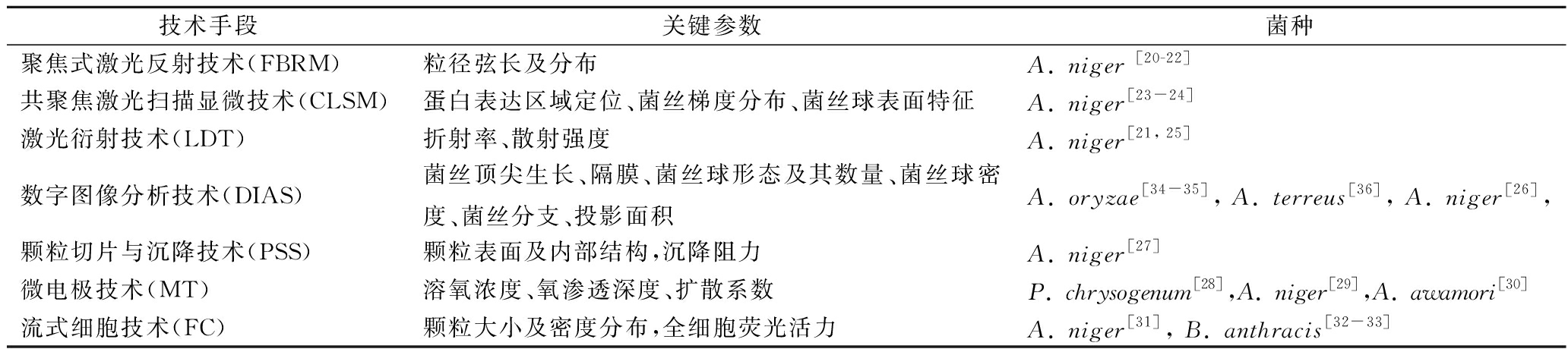

近年来,定量分析菌丝宏观形态学也取得了重要进展,一些新兴分析技术手段用于解析宏观形态学特征,如表2所示。聚焦式激光反射技术(focused beam reflectance measurement, FBRM),定量分析了黑曲霉颗粒弦长及其分布[20-22];共聚焦激光扫描显微技术(confocal laser scanning microscopy, CLSM),定量分析黑曲霉的菌丝球表面特征、菌丝梯度分布及其蛋白表达区域定位[23-24];激光衍射技术(laser diffraction technique, LDT),定量分析了黑曲霉的折射率和散射强度[21, 25];数字图像分析技术(digital image analysis system, DIAS),定量分析了菌丝顶尖生长、菌丝球形态及其数量,菌丝球最大直径及其密度[26]。颗粒切片与沉降技术(pellet slicing and sedimentation, PSS),定量分析了黑曲霉的菌丝球颗粒表面与内部结构及其沉降阻力[27]。微电极技术(microelectrode technique, MT),定量分析了Penicillium chrysogenum[28],A. niger[29],Aspergillus awamori[30]的溶氧浓度、渗透系数及其溶氧扩散深度。流式细胞技术(flow cytometry, FC),定量分析了A. niger[31],Bacillus anthracis[32-33]的菌丝球颗粒大小及密度分布,全细胞荧光活力。定量分析技术在丝状菌宏观形态学与微观形态学的发展,为深入理解发酵过程形态学特征变化规律,在工程水平上精确调控菌丝体形态,提高发酵效率奠定基础。

表2 菌体宏观形态学特征分析的研究进展

Table 2 Research advances in macroscopic morphological characteristics of strain

3 形态学工程

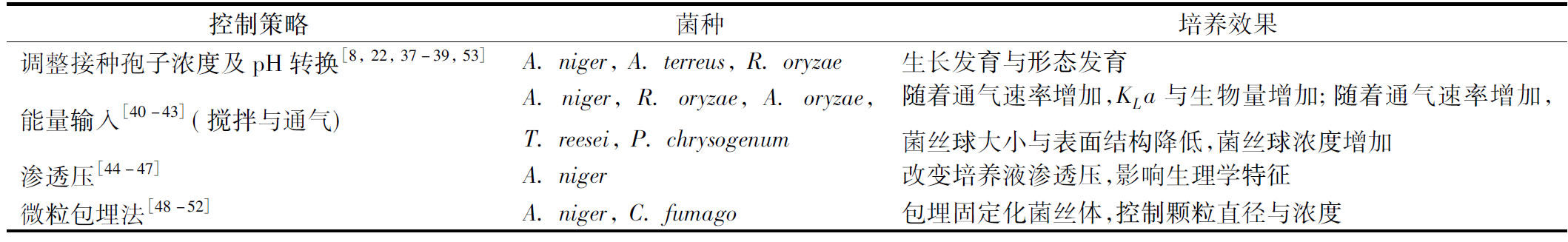

形态学分析手段的发展,为研究者在工程水平上控制菌丝特征提供了非常好的思路。环境条件会显著影响丝状菌的形态学特征[5],表3展示了过程水平上控制菌体形态学特征的研究报道。通过调整孢子接种量及转换pH的方法[8, 22, 37-39],基于菌体生长与群体效应,可以有效调控A. niger, Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus terreus, Rhizopus oryzae的形态学特征。通过调整通气与搅拌条件,改变发酵体系机械能量输入[40-43]。增加能量输入,体积溶氧系数(kLa)与生物量,成功用于调控A. niger, R. oryzae, A. oryzae, Trichoderma reesei, P. chrysogenum的菌丝球结构,菌丝球浓度增加,进而提升了发酵效率。基于调节渗透压[44-47],改变菌体的生理学特征,从而调整了A. niger的形态学特征。微粒包埋法[48-52],包埋固定化菌丝体,可以有效控制颗粒直径与浓度。形态学工程的蓬勃发展,为工业化控制丝状菌的发酵过程提供了借鉴。

表3 基于过程水平控制丝状菌形态学的研究进展

Table 3 Research progress in controning fungal morphology on the process level

在黑曲霉发酵柠檬酸生产中,研究专家详细分析了菌丝体的形态学特征,PAPAGIANNI[54-55]基于人工神经网络模型将菌丝体分为游离菌丝、菌丝块、菌丝球,并基于数字图像分析技术(DIAS)分析了不同孢子接种量条件下的菌丝体形态特征,发现调整孢子浓度可以有效调节菌丝聚集状态。在液体发酵体系中,搅拌对于改善溶氧与物质传递是非常重要的,但剧烈搅拌会产生剪切力,会引起菌丝体形态学变化[56]。PAPAGIANNI[57-58]发现搅拌在不同发酵阶段产生不同影响,在发酵初期剧烈搅拌会使菌丝高度分支化,产生菌丝碎片,而在发酵后期搅拌会使细胞老化,菌体衰亡。关于适合柠檬酸发酵的黑曲霉菌体形态学特征,不同研究专家存在不同的结果。PAUL[59],LEE[60]研究发现菌丝体形态以游离菌丝存在时,菌体比生长速率与比产酸速率明显高于菌丝球形态。KISSER [61],G MEZ[62]研究发现,菌丝体形态为菌丝球时产酸量更高。尽管适合柠檬酸发酵生产的菌丝体形态特征存在争议,但产酸较高的黑曲霉菌丝一般具有尖端多且膨大的特征,精确调控菌丝体形态有助于改善柠檬酸产量。

MEZ[62]研究发现,菌丝体形态为菌丝球时产酸量更高。尽管适合柠檬酸发酵生产的菌丝体形态特征存在争议,但产酸较高的黑曲霉菌丝一般具有尖端多且膨大的特征,精确调控菌丝体形态有助于改善柠檬酸产量。

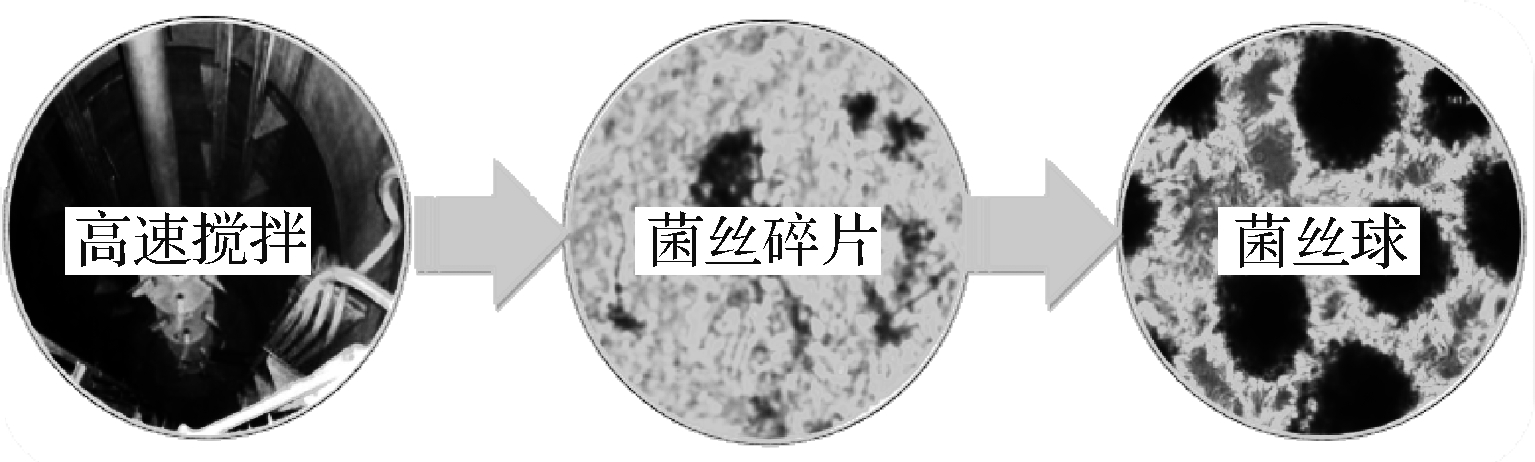

丝状菌在复杂的液体培养体系中,更易受到机械搅拌与通气等因素的影响,菌丝体形态呈现多样性,呈现从高度游离的分散菌丝到菌丝缠绕紧密的菌丝球的形态。剧烈搅拌引起的剪切力会改变菌体形态学特征并产生菌丝碎片。BELMAR-BEINY[63]利用Streptomyces clavuligerus发酵克拉维酸时,发现高搅拌产生的菌丝碎片重新生长并合成产物;PAPAGIANNI[58],PAUL[59]发现黑曲霉发酵生产柠檬酸时,机械剪切力能够将菌丝球表面的菌丝打散,形成的菌丝碎片会重新发育成菌丝球,如图3所示。XIN等[42]提出了采用研钵将菌丝球磨碎成菌丝碎片,菌丝碎片在一定培养条件下会重新缠绕成菌丝球,并成功应用于污水处理。上述丝状真菌整个生命周期形态学特征的研究进展,为精确调控与有效利用丝状真菌黑曲霉菌丝结构提供了启发;通过引入菌丝球分割技术,形成菌丝球—分散菌丝—菌丝球的循环模式,构建丝状真菌分割循环的新型发酵方式,可有效规避传统分批发酵模式能效低的缺陷。

图3 高速搅拌条件下的菌丝形态学特征

Fig.3 Morphological characteristics of mycelium under high speed stirring

4 结束语

高产量、高转化率、高生产强度统一为目标的发酵工程技术,一直是现代工业发酵关注的焦点问题。本文以黑曲霉发酵生产柠檬酸为代表,多维度解析了丝状菌在液态发酵体系中形态学特征及调控方法,并提出了基于现代仪器手段理解丝状菌的微观与宏观形态学特征,通过引入菌丝球分割技术,建立基于形态学工程的控制手段,精确调控与有效利用黑曲霉菌丝结构,进而建立适合柠檬酸发酵模式的形态学特征,为液态培养体系中丝状真菌形态塑造及其新型发酵模式构建提供一定参考。

参考文献

[1] 王宝石, 陈坚, 孙福新, 等. 发酵法生产柠檬酸的研究进展 [J]. 食品与发酵工业,2016, 42(9): 251-256.

[2] YIN X, LI J, SHIN H D, et al. Metabolic engineering in the biotechnological production of organic acids in the tricarboxylic acid cycle of microorganisms: advances and prospects [J]. Biotechnology Advances,2015, 33(6): 830-841.

[3] KUFORIJI O, KUBOYE A O, ODUNFA S A. Orange and pineapple wastes as potential substrates for citric acid production [J]. International Journal of Plant Biology,2010, 1(1): e1-e4.

[4] SOCCOL C R, VANDENBERGHE L P S, RODURIGUES C, et al. New perspectives for citric acid production and application [J]. Food Technology & Biotechnology,2006, 44(2): 141-149.

[5] KRULL R, WUCHERPFENNIG T, ESFANDABADI M E, et al. Characterization and control of fungal morphology for improved production performance in biotechnology [J]. Journal of Biotechnology,2013, 163(2): 112-123.

[6] BIZUKOJC M, LEDAKOWICZ S. Morphologically structured model for growth and citric acid accumulation by Aspergillus niger [J]. Enzyme and Microbial Technology,2003, 32(2): 268-281.

[7] POSCH A E, HERWIG C, SPADIUT O. Science-based bioprocess design for filamentous fungi [J]. Trends in Biotechnology,2013, 31(1): 37-44.

[8] PAPAGIANNI M. Fungal morphology and metabolite production in submerged mycelial processes [J]. Biotechnology Advances,2004, 22(3): 189-259.

[9] NIELSEN J. Modelling the morphology of filamentous microorganisms [J]. Trends in Biotechnology,1996, 14(11): 438-443.

[10] EMERSON S. The growth phase in neurospora corresponding to the logarithmic phase in unicellular organisms [J]. Journal of Bacteriology,1950, 60(3): 221-223.

[11] HERBRICH S, GEHDER M, KRULL R, et al. Label-free spatial analysis of free and enzyme-bound NAD(P)H in the presence of high concentrations of melanin [J]. Journal of Fluorescence,2012, 22(1): 349-355.

[12] WARGENAU A, KWADE A. Determination of adhesion between single Aspergillus niger spores in aqueous solutions using an atomic force microscope [J]. Langmuir,2010, 26(13): 11 071-11 076.

[13] FANG T H, KANG S H, HONG Z H, et al. Elasticity and nanomechanical response of Aspergillus niger spores using atomic force microscopy [J]. Micron,2012, 43(2-3): 407-411.

[14] TOUHAMI A, JERICHO M H, BEVERIDGE T J. Atomic force microscopy of cell growth and division in Staphylococcus Aureus [J]. Journal of Bacteriology,2004, 186(11): 3 286-3 295.

[15] ARFSTEN J, LEUPOLD S, BRADTMÖLLER C, et al. Atomic force microscopy studies on the nanomechanical properties of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae [J]. Colloids & Surfaces B Biointerfaces,2010, 79(1): 284-290.

[16] DYNESEN J, NIELSEN J. Surface hydrophobicity of Aspergillus nidulans conidiospores and its role in pellet formation [J]. Biotechnology Progress,2003, 19(3): 1 049-1 052.

[17] GALLARDO-MORENO A M, GONZ LEZ-MART

LEZ-MART N M L, PÉREZ-GIRALDO C, et al. Thermodynamic analysis of growth temperature dependence in the adhesion of Candida Parapsilosis to Polystyrene [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,2002,68(5): 2 610-2 613.

N M L, PÉREZ-GIRALDO C, et al. Thermodynamic analysis of growth temperature dependence in the adhesion of Candida Parapsilosis to Polystyrene [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,2002,68(5): 2 610-2 613.

[18] PRIEGNITZ B E, WARGENAU A, BRANDT U, et al. The role of initial spore adhesion in pellet and biofilm formation in Aspergillus niger[J]. Fungal genetics and biology, 2012, 49(1): 30-38.

[19] WARGENAU A, FLEIβNER A, BOLTEN C J, et al. On the origin of the electrostatic surface potential of Aspergillus niger spores in acidic environments [J]. Research in Microbiology,2011, 162(10): 1 011-1 017.

[20] HÖPFNER T, BLUMA A, RUDOLPH G, et al. A review of non-invasive optical-based image analysis systems for continuous bioprocess monitoring [J]. Bioprocess & Biosystems Engineering,2010, 33(2): 247-256.

[21] LEY I. Assessing resolution and sensitivity in a laser diffraction particle size analyser [J]. American Laboratory, 2000, 32(16):33-38.

[22] GRIMM L H, KELLY S, VÖLKERDING I I, et al. Influence of mechanical stress and surface interaction on the aggregation of Aspergillus niger Conidia [J]. Biotechnology and bioengineering,2005, 92(7): 879-888.

[23] HILLE A, NEU T R, HEMPEL D C, et al. Oxygen profiles and Biomass distribution in biopellets of Aspergillus niger [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering,2005, 92(5): 614-623.

[24] VILLENA G K, FUJIKAWA T, TSUYUMU S, et al. Structural analysis of biofilms and pellets of Aspergillus niger by confocal laser scanning microscopy and cryo scanning electron microscopy [J]. Bioresource Technology,2009, 101(6): 1 920-1 926.

[25] WUCHERPFENNIG T, LAKOWITZ A, KRULL R. Comprehension of viscous morphology—evaluation of fractal and conventional parameters for rheological characterization of Aspergillus niger culture broth [J]. Journal of Biotechnology,2013, 163(2): 124-132.

[26] BIZUKOJC M, LEDAKOWICZ S. A kinetic model to predict biomass content for Aspergillus niger germinating spores in the submerged culture [J]. Process Biochemistry, 2006, 41(5):1 063-1 071.

[27] LIN P J, SCHOLZ A, KRULL R. Effect of volumetric power input by aeration and agitation on pellet morphology and product formation of Aspergillus niger [J]. Biochemical Engineering Journal,2010, 49(2): 213-220.

[28] YANG S, LEWANDOWSKI Z. Measurement of local mass transfer coefficient in biofilms [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering,1995, 48(6): 737-744.

[29] HILLE A, NEU T R, HEMPEL D C, et al. Effective diffusivities and mass fluxes in fungal biopellets [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering,2009, 103(6): 1 202-1 213.

[30] CUI Y Q, VAN-DER-LANS R, LUYBEN K C A M. Effects of dissolved oxygen tension and mechanical forces on fungal morphology in submerged fermentation [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering,1998, 57(4): 409-419.

[31] DE-BEKKER C, VAN-VELUW G J, VINCK A, et al. Heterogeneity of Aspergillus niger microcolonies in liquid shaken cultures [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,2011, 77(4): 1 263-1 267.

[32] LAFLAMME C, VERREAULT D, LAVIGNE S, et al. Autofluorescence as a viability marker for detection of bacterial spores [J]. Frontiers in Bioscience,2005, 10(2): 1 647-1 653.

[33] TUNG J W, HEYDARI K, TIROUVANZIAM R, et al. Modern flow cytometry: A practical approach[J]. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine, 2007, 27(3): 453-468.

[34] BARRY D J, CHAN C, WILLIAMS G A. Morphological quantification of filamentous fungal development using membrane immobilization and automatic image analysis [J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology,2009, 36(6): 787-800.

[35] BARRY D J, WILLIAMS G A. Microscopic characterisation of filamentous microbes: Towards fully automated morphological quantification through image analysis [J]. Journal of Microscopy,2011, 244(1): 1-20.

[36] KOWALSKA A, BORUTA T, BIZUKOJ? M. Morphological evolution of various fungal species in the presence and absence of aluminum oxide microparticles: Comparative and quantitative insights into microparticle-enhanced cultivation (MPEC)[J]. MicrobiologyOpen, 2018, 7(5): e603-e619

[37] GRIMM L H, KELLY S, HENGSTLER J, et al. Kinetic studies on the aggregation of Aspergillus niger conidia [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering,2004, 87(2): 213-218.

[38] MAINWARING D O, WIEBE M G, ROBSON G D, et al. Effect of pH on hen egg white lysozyme production and evolution of a recombinant strain of Aspergillus niger [J]. Journal of Biotechnology,1999, 75(1): 1-10.

[39] TUCKER K G, KELLY T, DELGRAZIA P, et al. Fully-automatic measurement of mycelial morphology by image analysis [J]. Biotechnology Progress,1992, 8(4): 353-359.

[40] BIZUKOJC M, LEDAKOWICZ S. Physiological, morphological and kinetic aspects of lovastatin biosynthesis by Aspergillus terreus [J]. Biotechnology Journal,2009, 4(5): 647-664.

[41] AMANULLAH A, CHRISTENSEN L H, HANSEN K, et al. Dependence of morphology on agitation intensity in fed-batch cultures of Aspergillus oryzae and its implications for recombinant protein production [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering,2002, 77(7): 815-826.

[42] XIN B, XIA Y, ZHANG Y, et al. A feasible method for growing fungal pellets in a column reactor inoculated with mycelium fragments and their application for dye bioaccumulation from aqueous solution [J]. Bioresource Technology,2012, 105: 100-105.

[43] L PEZ J L C, P

PEZ J L C, P REZ J A S, SEVILLA J M F, et al. Pellet morphology, culture rheology and lovastatin production in cultures of Aspergillus terreus [J]. Journal of Biotechnology,2005, 116(1): 61-77.

REZ J A S, SEVILLA J M F, et al. Pellet morphology, culture rheology and lovastatin production in cultures of Aspergillus terreus [J]. Journal of Biotechnology,2005, 116(1): 61-77.

[44] WUCHERPFENNIG T, HESTLER T, KRULL R. Morphology engineering-osmolality and its effect on Aspergillus niger morphology and productivity [J]. Microbial Cell Factories,2011, 10(1): 58-73.

[45] BOBOWICZ-LASSOCISKA T, GRAJEK W. Changes in protein secretion of Aspergillus niger caused by the reduction of the water activity by potassium chloride [J]. Acta biotechnologica,1995, 15(3): 277-287.

[46] FIEDUREK J. Effect of osmotic stress on glucose oxidase production and secretion by Aspergillus niger[J]. Journal of Basic Microbiology: An International Journal on Biochemistry, Physiology, Genetics, Morphology, and Ecology of Microorganisms, 1998, 38(2): 107-112.

[47] WANG B, CHEN J, LI H, et al. Pellet-dispersion strategy to simplify the seed cultivation of Aspergillus niger and optimize citric acid production [J]. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering,2016,40(1):45-53.

[48] REN X D, XU Y J, ZENG X, et al. Microparticle-enhanced production of ε-poly-L-lysine in fed-batch fermentation [J]. Rsc Advances,2015, 5(100): 82 138-82 143.

[49] DRIOUCH H, SOMMER B, WITTMANN C. Morphology engineering of Aspergillus niger for improved enzyme production [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering,2010, 105(6): 1 058-1 068.

[50] DRIOUCH H, ROTH A, DERSCH P, et al. Optimized bioprocess for production of fructofuranosidase by recombinant Aspergillus niger [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology,2010, 87(6): 2 011-2 024.

[51] DRIOUCH H, ROTH A, DERSCH P, et al. Filamentous fungi in good shape: Microparticles for tailor-made fungal morphology and enhanced enzyme production [J]. Bioengineered Bugs,2011, 2(2): 100-104.

[52] DRIOUCH H, H NSCH R, WUCHERPFENNIG T, et al. Improved enzyme production by bio-pellets of Aspergillus niger : Targeted morphology engineering using titanate microparticles [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering,2012, 109(2): 462-471.

NSCH R, WUCHERPFENNIG T, et al. Improved enzyme production by bio-pellets of Aspergillus niger : Targeted morphology engineering using titanate microparticles [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering,2012, 109(2): 462-471.

[53] BIZUKOJC M, LEDAKOWICZ S. The morphological and physiological evolution of Aspergillus terreus mycelium in the submerged culture and its relation to the formation of secondary metabolites [J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology,2009, 26(1): 41-54.

[54] PAPAGIANNI M. Quantification of the fractal nature of mycelial aggregation in Aspergillus niger submerged cultures [J]. Microbial Cell Factories,2006, 5(1): 1-13.

[55] PAPAGIANNI M, MATTEY M. Morphological development of Aspergillus niger in submerged citric acid fermentation as a function of the spore inoculum level. Application of neural network and cluster analysis for characterization of mycelial morphology [J]. Microbial Cell Factories,2006, 5 (1): 3-15.

[56] PAPAGIANNI M, MATTEY M, KRISTIANSEN B. Morphology and citric acid production of Aspergillus niger PM 1 [J]. Biotechnology Letters,1994, 16(9): 929-934.

[57] PAPAGIANNI M, MATTEY M, KRISTIANSEN B. Citric acid production and morphology of Aspergillus niger as functions of the mixing intensity in a stirred tank and a tubular loop bioreactor [J]. Biochemical Engineering Journal,1998, 2(3): 197-205.

[58] PAPAGIANNI M, MATTEY M, KRISTIANSEN B. Hyphal vacuolation and fragmentation in batch and fed-batch culture of Aspergillus niger and its relation to citric acid production [J]. Process Biochemistry,1999, 35(3-4): 359-366.

[59] PAUL G C, PRIEDE M A, THOMAS C R. Relationship between morphology and citric acid production in submerged Aspergillus niger fermentations [J]. Biochemical Engineering Journal,1999, 3(2): 121-129.

[60] SEICHERT L, UJCOVA E, MUSILKOVA M, et al. Effect of aerationand agitation on the biosynthetic activity of diffusely growing Aspergillus niger [J]. Folia Microbiologica,1982, 27(5): 333-334.

[61] KISSER M, KUBICEK C P, RδHR M. Influence of manganese on morphology and cell wall composition of Aspergillus niger during citric acid fermentation [J]. Archives of Microbiology,1980, 128(1): 26-33.

[62] GδMEZ R, SCHNABEL I, GARRIDO J. Pellet growth and citric acid yield of Aspergillus niger 110 [J]. Enzyme and Microbial Technology,1988, 10(3): 188-191.

[63] BELMAR-BEINY M T, THOMAS C R. Morphology and clavulanic acid production of Streptomyces clavuligerus: effect of stirrer speed in batch fermentations [J]. Biotechnology and bioengineering,1991, 37(5): 456-462.