片球菌素的来源、生物合成、抑菌机理及其构效关系的研究进展

王祺1,张军1,乔晓妮1,何增国1,2*

1(中国海洋大学 医药学院,山东 青岛,266003) 2(青岛百奥安泰生物科技有限公司,山东 青岛,266100)

摘 要 片球菌素是除nisin外,在食品防腐领域距应用最近的一种细菌素,其具备安全、稳定、无残留的特点,特别在抑制李斯特菌方面潜力巨大。该文通过对已知片球菌素的来源、序列及结构特征、抑菌机理、构效关系的归纳,总结出其发挥抑菌作用的关键结构域和关键性氨基酸残基,为片球菌素的改造和工程化提供了理论基础。同时,就片球菌素在食品防腐领域的应用前景和存在的问题进行了深入探讨。

关键词 片球菌素;生物合成;抑菌机理;构效关系

DOI:10.13995/j.cnki.11-1802/ts.023260

引用格式:王祺,张军,乔晓妮,等.片球菌素的来源、生物合成、抑菌机理及其构效关系的研究进展[J].食品与发酵工业,2020,46(9):278-284.WANG Qi, ZHANG Jun, QIAO Xiaoni, et al. Research progress on pediocins: source, biosynthesis, bacteriostatic mechanism and structure-activity relationship[J].Food and Fermentation Industries,2020,46(9):278-284.

Research progress on pediocins: source, biosynthesis, bacteriostatic mechanism and structure-activity relationship

WANG Qi1, ZHANG Jun1, QIAO Xiaoni1, HE Zengguo1,2*

1(School of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China) 2(Qingdao Bioantai Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Qingdao 266100, China)

Abstract Pediocins are a group of bacteriocins produced by strains from genus Pediococcus. They have better potential to be used as food preservatives than nisin. Pediocins have some characteristics such as the safety, stability, residue-free natures. Specifically, they are well recognized for the control of Listeria monocytogenes. This paper summarized the source, sequence and structural characteristics of pediocins. Their bacteriostatic mechanism, structure-activity relationship and the core domains and key amino acid residues for bacteriostatic effects were addressed. This review provides a theoretical basis for engineering of pediocins and discusses the application prospects and the issues of pediocins in food preservative usage.

Key words pediocin; biosynthesis; bacteriostatic mechanism; structure-activity relationship

第一作者:硕士研究生(何增国教授为通讯作者,E-mail:bioantai88@vip.163.com)

基金项目:青岛市海洋生物医药科技创新中心建设专项(2017-CXZX01-5-3)

收稿日期:2020-01-05,改回日期:2020-03-01

李斯特菌(Listeria spp.)是一种导致食物腐败变质的常见微生物[1]。其中,单核增生李斯特菌(Listeria monocytogenes)更会引起动物和人类的疾病[2]。据世界卫生组织统计,4%~8%的水产品、5%~10%的乳及乳制品以及30%以上的肉类被李斯特菌污染[3]。人和动物误食被该菌污染的食品后,会引起严重的食物中毒[4]。据报道,美国每年有1600多例单核增生李斯特菌感染人的病例,死亡率高达12.5%[5]。虽然四环素、甲氧苄啶和青霉素对治疗单核增生李斯特菌中毒的效果显著,但在食品工业中,仍然缺乏安全防止单核增生李斯特菌污染的有效手段[6]。

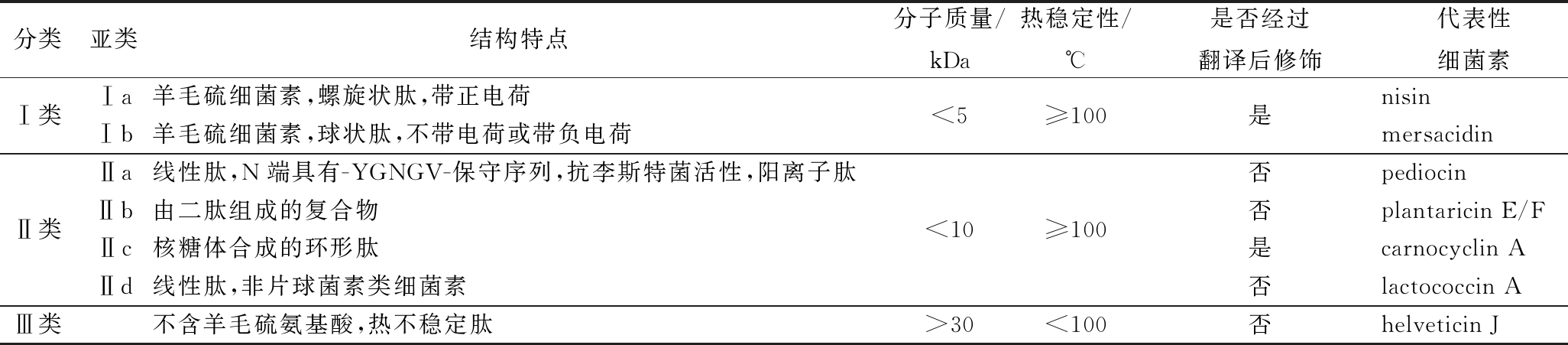

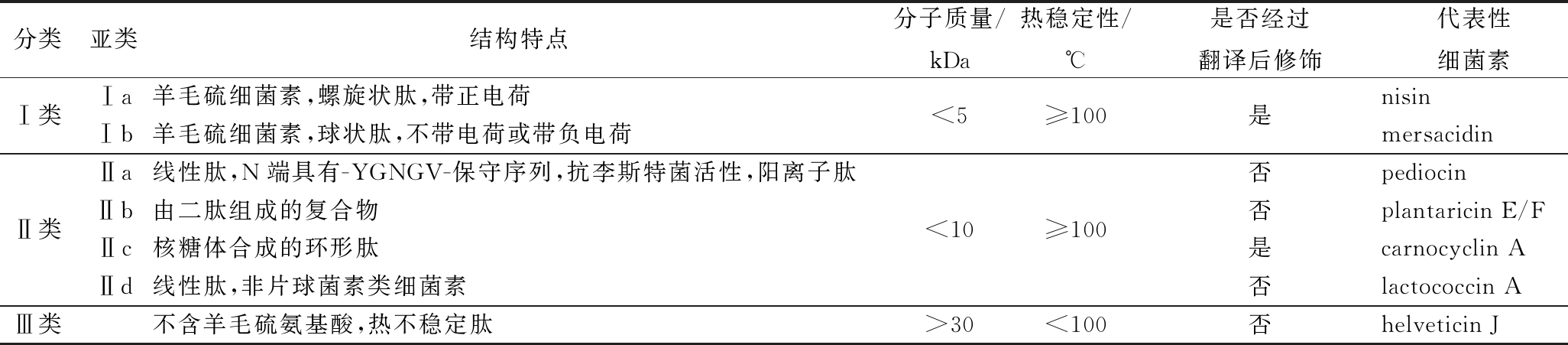

细菌素是一种来源于细菌的由核糖体合成具有抗菌功能的小肽,因具有安全性高、稳定性好、无残留等特点,在食品防腐领域日益受到关注[7]。乳酸菌是公认安全的(generally recognized as safe,GRAS)益生菌,其产生的细菌素更成为了食品防腐领域的研究热点[8]。其中,乳酸链球菌(Streptococcus lactis)代谢产生的细菌素——乳酸链球菌素(nisin)可有效地抑制腐败菌的生长、延长食品的保质期,已经在食品防腐领域应用达半个多世纪[9]。细菌素按照结构、分子量、热稳定性以及是否经过翻译后修饰等特点,主要分为3类(表1)。其中,IIa类细菌素也称类片球菌素,具有强烈的抗李斯特菌活性[10],其中以片球菌素(pediocin)最具代表性。片球菌素具有良好的热稳定性和广泛的pH适应性,能够满足苛刻的食品加工环境,因此在食品防腐领域,特别是防止李斯特菌污染方面,成为了继nisin之后,细菌素研究领域又一热点[11]。

表1 细菌素的分类

Table 1 Classification of bacteriocins

分类亚类结构特点分子质量/kDa热稳定性/℃是否经过翻译后修饰代表性细菌素Ⅰ类Ⅰa羊毛硫细菌素,螺旋状肽,带正电荷Ⅰb羊毛硫细菌素,球状肽,不带电荷或带负电荷<5≥100是nisinmersacidinⅡ类Ⅱa线性肽,N端具有-YGNGV-保守序列,抗李斯特菌活性,阳离子肽Ⅱb由二肽组成的复合物Ⅱc核糖体合成的环形肽Ⅱd线性肽,非片球菌素类细菌素<10≥100否pediocin否plantaricin E/F是carnocyclin A否lactococcin AⅢ类不含羊毛硫氨基酸,热不稳定肽>30<100否helveticin J

1 片球菌素的来源及序列特征

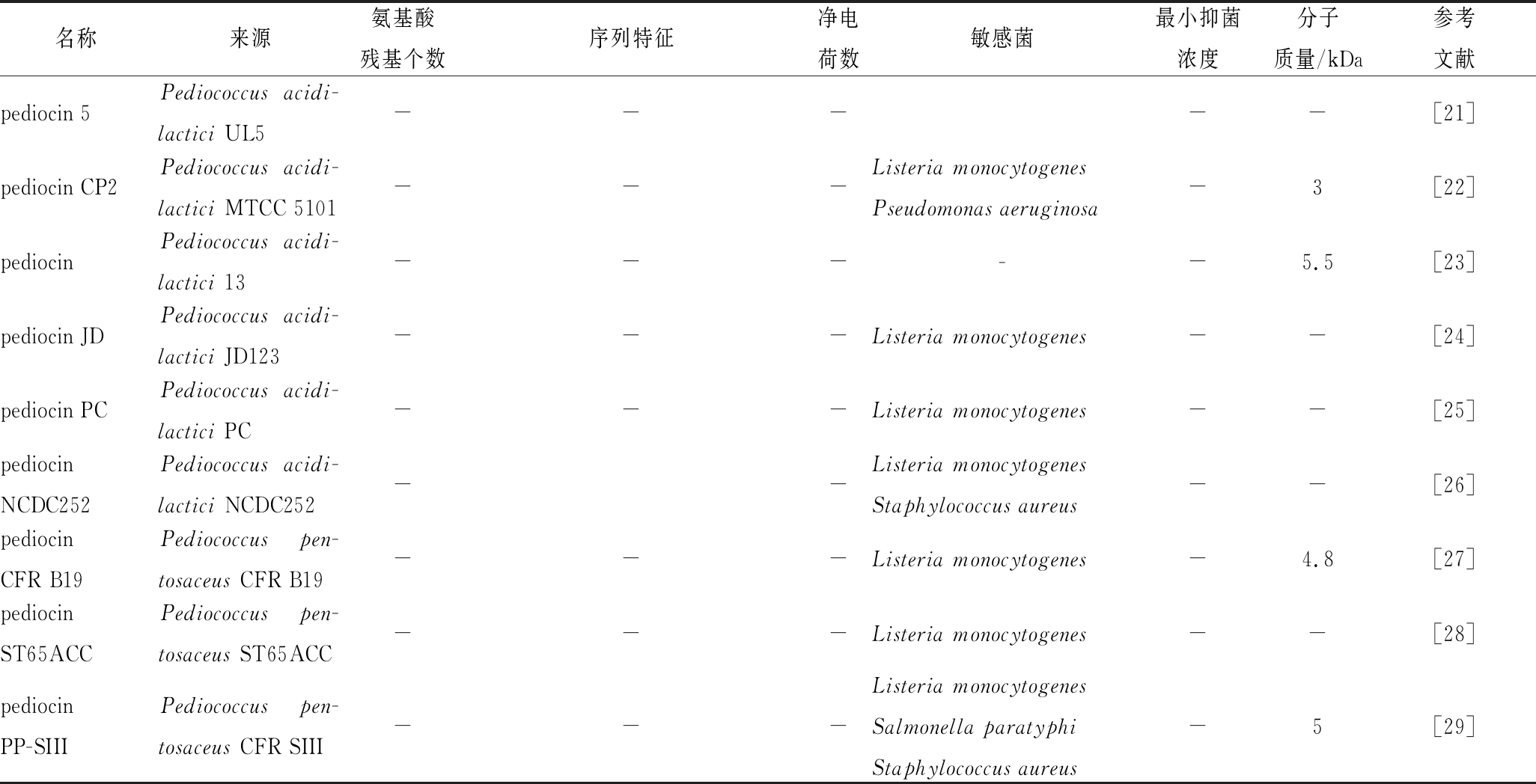

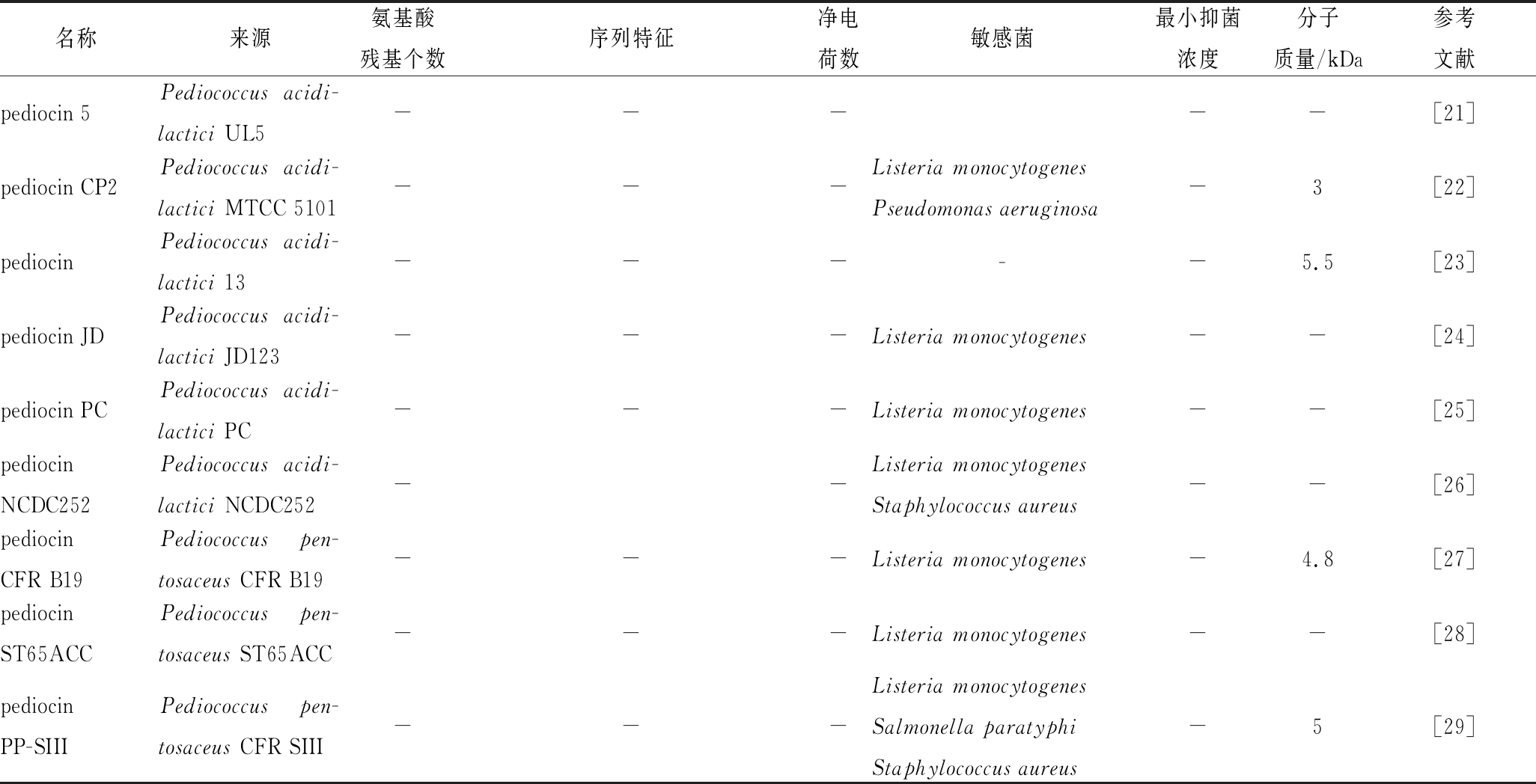

迄今为止,已发现的片球菌素共18个(表2),来源包括:乳酸片球菌(Pediococcus acidilactici)、戊糖片球菌(Pediococcus pentosaceous)和有害片球菌(Pediococcus damnosus)。片球菌素分子质量一般在2~10 kDa之间,其序列中氨基酸残基数量差异较大,从37~48个不等(除前导肽外),但其序列中均含有4个Cys,形成2对二硫键。如表2所示,片球菌素序列的净电荷数均为正值,这与其发挥抑菌功能直接相关。片球菌素一般在微克级别均有抑菌活性,且均表现出对单核增生李斯特菌具有强烈的抑制作用。

表2 片球菌素的种类及序列特征

Table 2 Types and sequence characteristics of pediocin

名称来源氨基酸残基个数序列特征净电荷数敏感菌最小抑菌浓度分子质量/kDa参考文献pediocin PA-1Pediococcus pen-tosaceous NCDC 27350ANIIGGKYYGNGVTCGKHSCSVD-WGKATTCIINNGAMAWATG-GHQGNHKC+3Listeria monocytogenesEnterococcus faecalis100 μmol/mL4.6[12-13]pediocin L50Pediococcus acidi-lactici L5041MGAIAKLVAKFGXXIV-VKYYKQIMQFIGQGVTINXIPLIXF+4Listeria monocytogenes278 ng/mL5.3[14]pediocin AcHPediococcus acidi-lactici H62MKKIEKLTEKEMANIIGGKYYG-NGVTCGKHSCSVDWGKATTCI-INNGAMAWATGGHQGNHKC+4Listeria monocytogenesStaphylococcus aureusClostridium perfringens2.7[15-16]pediocin APediococcus pen-tosaceus FBB6150ANIIGGKYYGNGVTCGKHSCSVD-WGKATTCIINNGAMAWATG-GHQGNHKC+3---[17]pediocin BPediococcus pen-tosaceus70MNKTKSEHIKQQALDLFTRLQ-FLLQKHDTIEPYQYVLDILET-GISKTKHNQQTPERQARV-VYNKIASQALV+3--GenBank: ASU08602.1pediocinAcMPediococcusacidilactici M---Staphylococcus aureusListeria monocytogenesBacillus coagulansBacillus cereusAeromonas hydrophilaClostridium perfringes5 μg/mL4.6[18]pediocinKJBC11Pediococcus pentosa-ceus KJBC11---Listeria monocytogenesStaphylococcus aureusAeromonas hydrophila15.6 μg/mL4.5[19]pediocinPD-1Pediococcus damno-sus NCFB 1832---Listeria monocytogenesOenococcus oeni850 μg/mL3.5[18-20]pediocin NV5Pediococcus acidi-lactici LAB5---Listeria monocytogenesStaphylococcus aureusStreptococcus mutans-10.3[2]

续表2

名称来源氨基酸残基个数序列特征净电荷数敏感菌最小抑菌浓度分子质量/kDa参考文献pediocin 5Pediococcus acidi-lactici UL5-----[21]pediocin CP2Pediococcus acidi-lactici MTCC 5101---Listeria monocytogenesPseudomonas aeruginosa-3[22]pediocinPediococcus acidi-lactici 13-----5.5[23]pediocin JDPediococcus acidi-lactici JD123---Listeria monocytogenes--[24]pediocin PCPediococcus acidi-lactici PC---Listeria monocytogenes--[25]pediocinNCDC252Pediococcus acidi-lactici NCDC252--Listeria monocytogenesStaphylococcus aureus--[26]pediocinCFR B19Pediococcus pen-tosaceus CFR B19---Listeria monocytogenes-4.8[27]pediocin ST65ACCPediococcus pen-tosaceus ST65ACC---Listeria monocytogenes--[28]pediocinPP-SIIIPediococcus pen-tosaceus CFR SIII---Listeria monocytogenesSalmonella paratyphiStaphylococcus aureus-5[29]

2 片球菌素的生物合成

片球菌素的合成基因由质粒编码,其合成和分泌相关的4个基因位于同一操纵子[30],包括:(1)结构基因(structural genes),用于编码片球菌素前体;(2)免疫基因(immunity genes),用于编码保护片球菌素产生菌免受其自身杀死的免疫蛋白;(3)ABC转运蛋白系统基因(ATP-bindingcassette transporter system genes),用于编码与细胞膜相关的ABC转运蛋白系统,该系统将片球菌素转移到细胞膜上,同时去除片球菌素前体的前导序列;(4)辅助蛋白基因(accessory protein genes),用于编码片球菌素分泌所必需的辅助蛋白。

与众多细菌素的合成类似,片球菌素的生物合成同样受群体感应(quorum sensing,QS)系统调控,主要表现在细菌素表达量与细胞密度或环境压力正相关[31]。这一过程受3组分系统调控[7],即(1)诱导因子(inducer factor, IF);(2)膜组氨酸蛋白激酶(member histidine protein kinase, MHK);(3)响应调节因子(response regulator, RR)。首先,IF在基础水平上进行组成型表达,并通过ABC转运蛋白系统分泌到细胞外,当释放到细胞外的IF浓度足够高时,会结合到跨膜的MHK上,使其位于细胞质一侧自磷酸化。之后,这个磷酸基被转移到RR,并激活RR。最后,活化的RR与片球菌素结构基因上的启动子结合,启动片球菌素基因的表达。其中,IF在片球菌素生物合成过程作为正反馈因子,促进其自动调节机制(图1)。

片球菌素基因表达的特点主要在于其N端有一段前导肽。该前导肽可使片球菌素前体与ABC转运蛋白系统有效互作。然后,在成熟的片球菌素分泌到胞外前,前导肽在细胞质侧被ABC转运蛋白系统的附属蛋白降解。此外,与其他细菌素的前体通常不具活性相比,连接前导肽片段的片球菌素前体具有明显的抑菌活性[32]。因此,为了避免片球菌素对产生菌的抑制作用,片球菌素合成后会被迅速运输到胞外(图1)。然而,前导肽的作用仅为辅助片球菌素分泌,对结构域的形成和抑菌功能的实现并没有作用。RAY等[32]将pediocin AcH前体肽和成熟肽分别进行异源表达,结果发现pediocin AcH前体肽的抑菌活性约为成熟肽的80%,这表明前导肽对pediocin AcH成熟结构域的形成和抑菌作用几乎没有影响。

3 片球菌素的抑菌机理

3.1 正确构象的形成

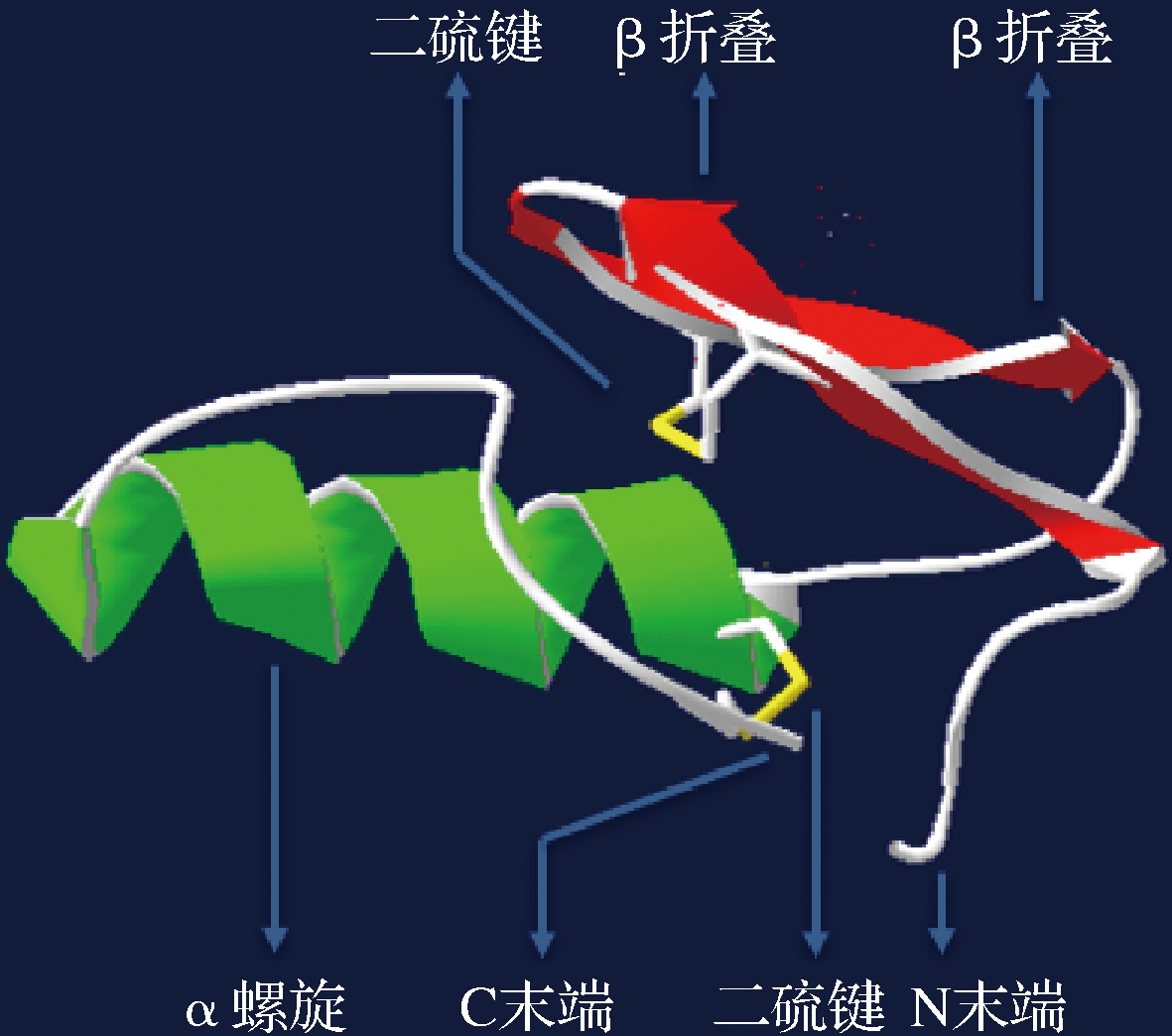

分泌到细胞外的片球菌素需要在特定环境条件下才能形成正确构型。研究发现,类片球菌素sakacin P在水或二甲基亚砜溶液中均以无规卷曲存在,不能正确折叠[33]。片球菌素正确折叠通常依赖于细胞膜或与细胞膜类似的环境。CASTANHO等[34]利用十二烷基磷酸胆碱(DPC)胶束和三氟乙醇(TFE)溶液模拟细胞膜环境,使用核磁共振波谱法分析2种类片球菌素在该环境下的三维结构,结果显示,N端形成含有二硫键的三股反平行β-折叠,同时C末端折回至中心α-螺旋上,形成含有发夹状结构的正确构型。这种受细胞膜或类细胞膜环境催化的折叠方式,拉近了带正电荷氨基酸残基的空间位置,为细菌素更好的与靶细胞膜结合提供了高效的构象基础。

3.2 N端与细胞膜的吸附结合

形成正确构型的片球菌素,通过N端β折叠结构域与目标菌株的细胞膜相互结合。首先,该结构域中带正电荷氨基酸残基通过非特异性的静电引力与靶细胞膜上带负电荷的磷脂基团相互作用,使片球菌素的亲水部分固定于细胞膜上[35]。因此,β折叠结构域带中正电荷氨基酸残基的聚集区越多,片球菌素对靶细胞膜的亲和力和结合力越强[36];随后,该结构域与靶细胞膜上的甘露糖磷酸转移酶系统(mannose phosphotransferase system, man-PTS)结合,锚定在细胞膜上[37]。

3.3 C端向膜内插入

片球菌素锚定于细胞膜上后,其C端疏水性螺旋自然向细胞膜中间的疏水性区域插入,而C端区域插入的具体位置,由靶细胞膜上man-PTS的ⅡC和ⅡD亚基决定。首先,C端螺旋结构在片球菌素插入靶细胞膜时可作为跨膜组分起作用,即疏水螺旋穿入靶细胞膜的疏水核心。随后,特异性结合man-PTS的ⅡC和ⅡD亚基,导致细胞膜穿孔[38]。在膜穿孔过程中,片球菌素与II C亚基特异性结合形成片球菌素-II C复合物,而II D亚基起到稳定该复合物结构的作用。KJOS等[39] 在大肠杆菌中对单核增生李斯特菌的man-PTS的ⅡC和ⅡD亚基进行异源表达后发现,ⅡC亚基单独表达时和ⅡC和ⅡD亚基共表达情况下,其对片球菌素敏感,且敏感性后者是前者的2倍,而当对ⅡD亚基单独表达时,大肠杆菌对片球菌素不敏感。因此,稳定的片球菌素-IIC复合物的形成,对片球菌素抑菌功能的实现起到至关重要的作用。

3.4 在细胞膜上穿孔形成孔洞

片球菌素在靶细胞膜上形成孔洞后,直接导致胞内钾离子、氨基酸等小分子物质外泄,使跨膜细胞质子动能势(proton-motive force, PMF)丧失。MANDAL等[2]利用800 AU/mL的pediocin NV5对单核增生李斯特菌处理30 min后发现,溶液中钾离子浓度提高7.5倍。然而,片球菌素作用于敏感细胞膜形成的孔洞直径较小,ATP和蛋白质等大分子物质会被截留在胞内,PMF的丧失加速了胞内ATP的消耗,导致细胞凋亡[40]。

4 片球菌素的构效关系

Ⅱa类细菌素是以片球菌素的结构为基础归类的,其一级结构通常包含37~48个氨基酸残基,亲水的阳离子N端区域含有1个保守的片球菌素框(pediocin box)区域,包含-YGNGV-基序[41-42]。二级结构中N端区域通常形成β-折叠结构域,C端结构域由1~2个α螺旋组成两亲性或疏水性结构。三级结构中C端通常以一个结构延伸的尾部折叠形成发夹状,在β折叠的N末端区域和发夹状C末端区域之间有1个柔性铰链,可使2个结构域之间实现相对移动[43]。大多数Ⅱa类细菌素N端均存在一对二硫键,对维持N端的两亲性结构和β折叠结构域的稳定具有重要作用(图2)。

与Ⅱa类细菌素不同的是,片球菌素通常在其C端存在另一个二硫键,这使得片球菌素相对于其他Ⅱa类细菌素结构更加稳定[38-44]。FIMLAND等[45]发现,同为Ⅱa类细菌素,C端含二硫键的pediocin PA-1与C端不含二硫键的sakacin P相比,虽然在20 ℃的条件下抑菌活性相同,但在37 ℃条件下,前者的抑菌活性为后者的10倍。

4.1 C端区域

C末端α螺旋结构对片球菌素发挥抑菌功能起着决定性作用,因此对该区域序列中的关键氨基酸残基进行替代研究,可以有效提高片球菌素的抑菌功能。FIMLAND等[46]通过组合不同IIa类细菌素N端和C端区域,形成系列杂合细菌素。通过抑菌实验发现,C末端相同的杂合肽其抑菌功能大体相同,而N末端相同的杂合肽抑菌活性差异巨大;C末端的抑菌活性与其氨基酸残基组成直接相关。SUN等[47]通过对pediocin PA-1 C末端区域中8个氨基酸残基进行突变,结果显示,用疏水性氨基酸残基Ala取代第29位的Gly后,抑菌活性有非常明显的增加;HAUGEN等[48]利用带负电荷的氨基酸残基Asp替换pediocin PA-1 C末端一半螺旋区的片段中的所有残基,结果表明,第20位的Lys被替代后,片球菌素抑制活性有明显的降低。因此,疏水性和带正电荷的氨基酸残基,与C末端发挥抑菌作用直接相关。

4.2 N端区域

N端区域直接参与片球菌素与靶细胞膜结合。因此,对该区域序列中的关键氨基酸残基进行替代研究,可使片球菌素与靶细胞更有效的结合,而更高的结合效率通常意味着发挥抑菌作用需要的浓度更低。SONG等[49]对pediocin PA-1 N端正电荷氨基酸残基进行插入和替代研究,结果发现,将其N端第0位插入1个带正电荷的Lys,同时将第13位的Ser替换为Lys后,片球菌素突变体对靶细胞的亲和力升高,且对单核增生李斯特菌的抑菌浓度降低了50%,而在N端第10位的Gly替换为Lys后,片球菌素变体对靶细胞的亲和力降低,其抑菌浓度增加了10倍之多。因此,增加片球菌素N端特定位置带正电荷氨基酸残基,对其发挥抑菌功能具有提升作用。

4.3 ABC转运蛋白和辅助蛋白

ABC转运蛋白是保证片球菌素向胞外分泌的关键。该蛋白由约700个氨基酸残基组成,参与前导肽切割和成熟片球菌素向胞外分泌。因此,其结构稳定性对其发挥转运功能至关重要,二硫键通常具有维持蛋白结构稳定性的作用。OPPEGÅRD等[50]用Ser替代pediocin PA-1 ABC转运蛋白的Cys,结果显示pediocin PA-1向胞外的分泌被完全抑制。这表明ABC转运蛋白结构的稳定对其发挥转运片球菌素的功能至关重要。

片球菌素通常具有1~2对二硫键,辅助蛋白通常参与片球菌素二硫键的形成。辅助蛋白通常包含170个氨基酸残基,其N端依靠2个Cys形成的1对二硫键维持结构稳定。HAVARSTEIN等[51]分别用Ser替换pediocin PA-1辅助蛋白中的2个Cys,结果发现,取代第86位Cys后形成正确二硫键pediocin PA-1的数量减少到之前的1/2,而取代第83位Cys后形成正确二硫键连接的pediocin PA-1几乎完全消失。因此,辅助蛋白参与片球菌素二硫键的形成过程,同样依赖于其结构的稳定性。

5 展望

近年来,生物防腐剂受到了越来越多的关注[52]。片球菌素作为一种高效、安全、无毒、无残留的天然防腐剂,符合未来食品防腐领域的发展需求。片球菌素可强烈且专一抑制食物腐败菌——李斯特菌,其较窄的抗菌谱可能意味着更强的靶向性且对人体微生态的平衡影响更小。目前,已知的片球菌素产生菌均为GRAS菌,即公认的安全性菌种。片球菌素优良的热耐受性使其可被广泛的用于需经热处理的食品,而其广泛的pH耐受性,有效弥补了目前唯一商业化细菌素nisin仅存在于低pH值条件下的不足。片球菌素无毒、无色、无味,这些特点使其在食品领域发挥防腐作用的同时,不影响食物的风味,而蛋白属性又决定了其可被肠道内的胰蛋白酶等降解,因此不必担心残留和环境释放问题。未来,片球菌素作为食品添加剂大规模应用于食品工业,还有待于以下方面研究的进展:(1)高产片球菌素菌株的选育;(2)片球菌素专一性抑制李斯特菌机理的阐明;(3)利用分子手段,优化片球菌素序列结构,提高抗菌活性;(4)探索片球菌素在不同的食品加工环境和工艺下的应用效果。同时,开展片球菌素与其他防腐手段,如高流体静压或脉冲电场等协同作用的抑菌效果研究,也将拓宽其应用范围。相信随着相关研究的不断深入,片球菌素在食品领域,防止李斯特菌侵染方面将发挥重要的作用。

参考文献

[1] SCHUPPLER M, LOESSNER M J. The opportunistic pathogen Listeria monocytogenes: pathogenicity and interaction with the mucosal immune system[J]. International Journal of Inflammation, 2010:1-12.DOI:10.4061/2010/704321

[2] MANDAL V, SEN S K, MANDAL N C. Assessment of antibacterial activities of pediocin produced by Pediococcus acidilactici LAB 5[J]. Journal of Food Safety, 2010, 30(3):635-651.

[3] 于凯慧. 奶酪关键致病菌安全的生物控制研究[D]. 哈尔滨:东北农业大学, 2011.

[4] OHK S H, BHUNIA A K. Multiplex fiber optic biosensor for detection of Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica from ready-to-eat meat samples[J]. Food Microbiology, 2013, 33(2):166-171.

[5] 申海鹏. 李斯特菌的危害[J]. 食品安全导刊, 2015(Z1):36-39.

[6] ESCOLAR C, G MEZ D, DEL CARMEN ROTA GARC

MEZ D, DEL CARMEN ROTA GARC A M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua isolated from ready-to-eat products of animal origin in Spain[J]. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 2017, 14(6):357-363.

A M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua isolated from ready-to-eat products of animal origin in Spain[J]. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 2017, 14(6):357-363.

[7] PORTO M C W, KUNIYOSHI T M, AZEVEDO P O S, et al. Pediococcus spp.: An important genus of lactic acid bacteria and pediocin producers[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2017, 35(3):361-374.

[8] DE-CASTILHO N P A, NERO L A, TODOROV S D. Molecular screening of beneficial and safety determinants from bacteriocinogenic lactic acid bacteria isolated from Brazilian artisanal calabresa[J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2019, 69(3):204-211.

[9] GHARSALLAOUI A, JOLY C, OULAHAL N, et al. Nisin as a food preservative: part 2: antimicrobial polymer materials containing nisin[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2016, 56(8):1 275-1 289.

[10] MARWATI T, CAHYANINGRUM N, WIDODO S, et al. Inhibitory activity of bacteriocin produced from Lactobacillus SCG 1223 toward L. monocytogenes, S. thypimurium and E. coli[J]. IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science, 2018, 102(1):012091.

[11] BALANDIN S V, SHEREMETEVA E V, BIOCHEMISTRY T V. Pediocin-like antimicrobial peptides of bacteria[J]. Biochemistry, 2019, 84(5):464-478.

[12] VIJAY SIMHA V, SOOD S K, KUMARIYA R, et al. Simple and rapid purification of pediocin PA-1 from Pediococcus pentosaceous NCDC 273 suitable for industrial application[J]. Microbiological Research, 2012, 167(9):544-549.

[13] RODRI GUEZ E, CALZADA J, ARQUÉS J L, et al. Antimicrobial activity of pediocin-producing Lactococcus lactis on Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cheese[J]. International Dairy Journal, 2005, 15(1):51-57.

GUEZ E, CALZADA J, ARQUÉS J L, et al. Antimicrobial activity of pediocin-producing Lactococcus lactis on Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cheese[J]. International Dairy Journal, 2005, 15(1):51-57.

[14] CINTAS L M, RODRIGUEZ J M, FERNANDEZ M F, et al. Isolation and characterization of pediocin L50, a new bacteriocin from Pediococcus acidilactici with a broad inhibitory spectrum[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1995, 61(7):2 643-2 648.

[15] MOTLAGH A M, BHUNIA A K, SZOSTEK F, et al. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence of pap-gene (pediocin AcH production) in Pediococcus acidilactici H[J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 1992, 15(2):45-48.

[16] BHUNIA A K, JOHNSON M C, RAY B. Purification, characterization and antimicrobial spectrum of a bacteriocin produced by Pediococcus acidilactici[J]. Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 1988, 65(4):261-268.

[17] KLERK H C D, SMIT J A. Properties of a Lactobacillus fermenti bacteriocin[J]. Journal of General Microbiology, 1967, 48(2):309-316.

[18] ELEGADO F B, KIM W J, MICROBIOLOGY D Y. Rapid purification, partial characterization, and antimicrobial spectrum of the bacteriocin, pediocin AcM, from Pediococcus acidilactici M[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 1997, 37(1):1-11.

[19] SADISHKUMAR V, JEEVARATNAM K. Purification and partial characterization of antilisterial bacteriocin produced by Pediococcus pentosaceus KJBC11 from Idli batter fermented with piper betle leaves[J]. Journal of Food Biochemistry, 2017, 42(1):e12460.

[20] GREEN G, DICKS L M, BRUGGEMAN G, et al. Pediocin PD1, a bactericidal antimicrobial peptide from Pediococcus damnosus NCFB 1832[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 1997, 83(1):127-132.

[21] HUANG J, LACROIX C, DABA H, et al. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes in milk and its control by pediocin 5 produced by Pediococcus acidilactici UL5[J]. International Dairy Journal, 1994, 4(5):429-443.

[22] KAUR B, BALGIR P P. Biopreservative potential of a broad-range pediocin CP2 obtained from Pediococcus acidilactici MTCC 5101[J]. Asian Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Environmental Science, 2008, 10(2):439-444.

[23] ALTUNTA E G, AYHAN K, PEKER S, et al. Purification and mass spectrometry based characterization of a pediocin produced by Pediococcus acidilactici 13[J]. Molecular Biology Reports, 2014, 41(10):6 879-6 885.

E G, AYHAN K, PEKER S, et al. Purification and mass spectrometry based characterization of a pediocin produced by Pediococcus acidilactici 13[J]. Molecular Biology Reports, 2014, 41(10):6 879-6 885.

[24] BERRY E D, HUTKINS R W, MANDIGO R W. The use of bacteriocin-producing Pediococcus acidilactici to control postprocessing Listeria monocytogenes contamination of frankfurters[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 1991, 54(9):681-686.

[25] NETTLES C G, BAREFOOT S F. Biochemical and genetic characteristics of bacteriocins of food-associated lactic acid bacteria[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 1993, 56(4):338-356.

[26] KAMBLE P K, RAO V A, ABRAHAM R J J, et al. Assessment of antibacterial activity of pediocin NCDC252 produced from Pediococus acidilactici NCDC252 and study of its effect on physico-chemical properties of chicken carcasses stored at refrigeration temperature[J]. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci, 2017,6(7):2 256-2 268.

[27] VENKATESHWARI S, HALAMI P, VIJAYENDRA S V. Characterisation of the heat-stable bacteriocin-producing and vancomycin-sensitive Pediococcus pentosaceus CFR B19 isolated from beans[J]. Beneficial Microbes, 2010, 1(2):159-164.

[28] CAVICCHIOLI V Q, CAMARGO A C, TODOROV S D, et al. Novel bacteriocinogenic Enterococcus hirae and Pediococcus pentosaceus strains with antilisterial activity isolated from Brazilian artisanal cheese[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2017, 100(4):2 526-2 535.

[29] HALAMI P M, BADARINATH V, DEVI S M, et al. Partial characterization of heat-stable, antilisterial and cell lytic bacteriocin of Pediococcus pentosaceus CFR SIII isolated from a vegetable source[J]. Annals of Microbiology, 2011, 61(2):323-330.

[30] MESA-PEREIRA B, O’CONNOR P M, REA M C, et al. Controlled functional expression of the bacteriocins pediocin PA-1 and bactofencin A in Escherichia coli [J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7:3 069.

[31] WAYAH S B, PHILIP K. Pentocin MQ1: A novel, broad-spectrum, pore-forming bacteriocin from Lactobacillus pentosus CS2 with quorum sensing regulatory mechanism and biopreservative potential [J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9:564.

[32] RAY B, SCHAMBER R, MILLER K W. The pediocin ACH precursor is biologically active[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1999, 65(6):2 281-2 286.

[33] MEHTA R, ARYA A, GOYAL K, et al. Bio-preservative and therapeutic potential of pediocin: recent trends and future perspectives [J]. Recent Patents on Biotechnology, 2013, 7(3):172-178.

[34] CASTANHO M A, FERNANDES M X. Lipid membrane-induced optimization for ligand-receptor docking: recent tools and insights for the “membrane catalysis” model[J]. European Biophysics Journal, 2006, 35(2):92-103.

[35] R OS COLOMBO N S, CHAL

OS COLOMBO N S, CHAL N M C, NAVARRO S A, et al. Pediocin-like bacteriocins: new perspectives on mechanism of action and immunity[J]. Current Genetics, 2018, 64(2):345-351.

N M C, NAVARRO S A, et al. Pediocin-like bacteriocins: new perspectives on mechanism of action and immunity[J]. Current Genetics, 2018, 64(2):345-351.

[36] KJOS M, BORRERO J, OPSATA M, et al. Target recognition, resistance, immunity and genome mining of class II bacteriocins from Gram-positive bacteria[J]. Microbiology (Reading, England), 2011, 157(12):3 256-3 267.

[37] BARRAZA D E, R OS COLOMBO N S, GALV

OS COLOMBO N S, GALV N A E, et al. New insights into enterocin CRL35: mechanism of action and immunity revealed by heterologous expression in Escherichia coli[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 2017, 105(6):922-933.

N A E, et al. New insights into enterocin CRL35: mechanism of action and immunity revealed by heterologous expression in Escherichia coli[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 2017, 105(6):922-933.

[38] OPSATA M, NES I F, HOLO H. Class IIa bacteriocin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis V583: the mannose PTS operon mediates global transcriptional responses [J]. BMC Microbiology, 2010, 10:224.

[39] KJOS M, SALEHIAN Z, NES I F, et al. An extracellular loop of the mannose phosphotransferase system component IIc is responsible for specific targeting by class IIa bacteriocins[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2010, 192(22):5 906-5 913.

[40] COTTER P D, ROSS R P, HILL C. Bacteriocins - a viable alternative to antibiotics? [J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2013, 11(2):95-105.

[41] ETAYASH H, AZMI S, DANGETI R, et al. Peptide bacteriocins-structure activity relationships[J]. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 2016, 16(2):220-241.

[42] CHIKINDAS M L, WEEKS R, DRIDER D, et al. Functions and emerging applications of bacteriocins[J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2018, 49:23-28.

[43] CUI Y, ZHANG C,WANG Y F, et al. Class IIa bacteriocins: Diversity and new developments[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2012, 13(12):16 668-16 707.

[44] 张健. 乳酸片球菌细菌素的发酵与纯化研究[D]. 天津:天津大学, 2012.

[45] FIMLAND G, JOHNSEN L, AXELSSON L, et al. A C-terminal disulfide bridge in pediocin-like bacteriocins renders bacteriocin activity less temperature dependent and is a major determinant of the antimicrobial spectrum[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2000, 182(9):2 643-2 648.

[46] FIMLAND G, BLINGSMO O R, SLETTEN K, et al. New biologically active hybrid bacteriocins constructed by combining regions from various pediocin-like bacteriocins: the C-terminal region is important for determining specificity[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1996, 62(9):3 313-3 318.

[47] SUN L, SONG H, ZHENG W. Improvement of antimicrobial activity of pediocin PA-1 by site-directed mutagenesis in C-terminal domain[J]. Protein Peptide Letters, 2015, 22(11):1 007-1 012.

[48] HAUGEN H S, FIMLAND G, NISSEN-MEYER J. Mutational analysis of residues in the helical region of the class IIa bacteriocin pediocin PA-1[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(6):1 966-1 972.

[49] SONG D F, LI X, ZHANG Y H, et al. Mutational analysis of positively charged residues in the N-terminal region of the class IIa bacteriocin pediocin PA-1[J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2014, 58(4):356-361.

[50] OPPEGÅRD C, FIMLAND G, ANONSEN J H, et al. The pediocin PA-1 accessory protein ensures correct disulfide bond formation in the antimicrobial peptide pediocin PA-1[J]. Biochemistry, 2015, 54(19):2 967-2 974.

[51] HAVARSTEIN L S, DIEP D B, NES I F. A family of bacteriocin ABC transporters carry out proteolytic processing of their substrates concomitant with export[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 1995, 16(2):229-240.

[52] MARTINEZ F A, BALCIUNAS E M, CONVERTI A, et al. Bacteriocin production by Bifidobacterium spp. A review[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2013, 31(4):482-488.

MEZ D, DEL CARMEN ROTA GARC

MEZ D, DEL CARMEN ROTA GARC A M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of

A M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of  E G, AYHAN K, PEKER S, et al. Purification and mass spectrometry based characterization of a pediocin produced by

E G, AYHAN K, PEKER S, et al. Purification and mass spectrometry based characterization of a pediocin produced by  N A E, et al. New insights into enterocin CRL35: mechanism of action and immunity revealed by heterologous expression in

N A E, et al. New insights into enterocin CRL35: mechanism of action and immunity revealed by heterologous expression in